- General Dermatology

- Eczema

- Alopecia

- Aesthetics

- Vitiligo

- COVID-19

- Actinic Keratosis

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Rare Disease

- Wound Care

- Rosacea

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Skin Cancer

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Drug Watch

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Acne

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Practice Management

I Am Not Being Paid to Treat Actinic Keratoses: How Could That Be?

This month's Legal Eagle column highlights the tension between cost control measures and concerns about patient care in the context of health care spending and the increasing prevalence of actinic keratoses

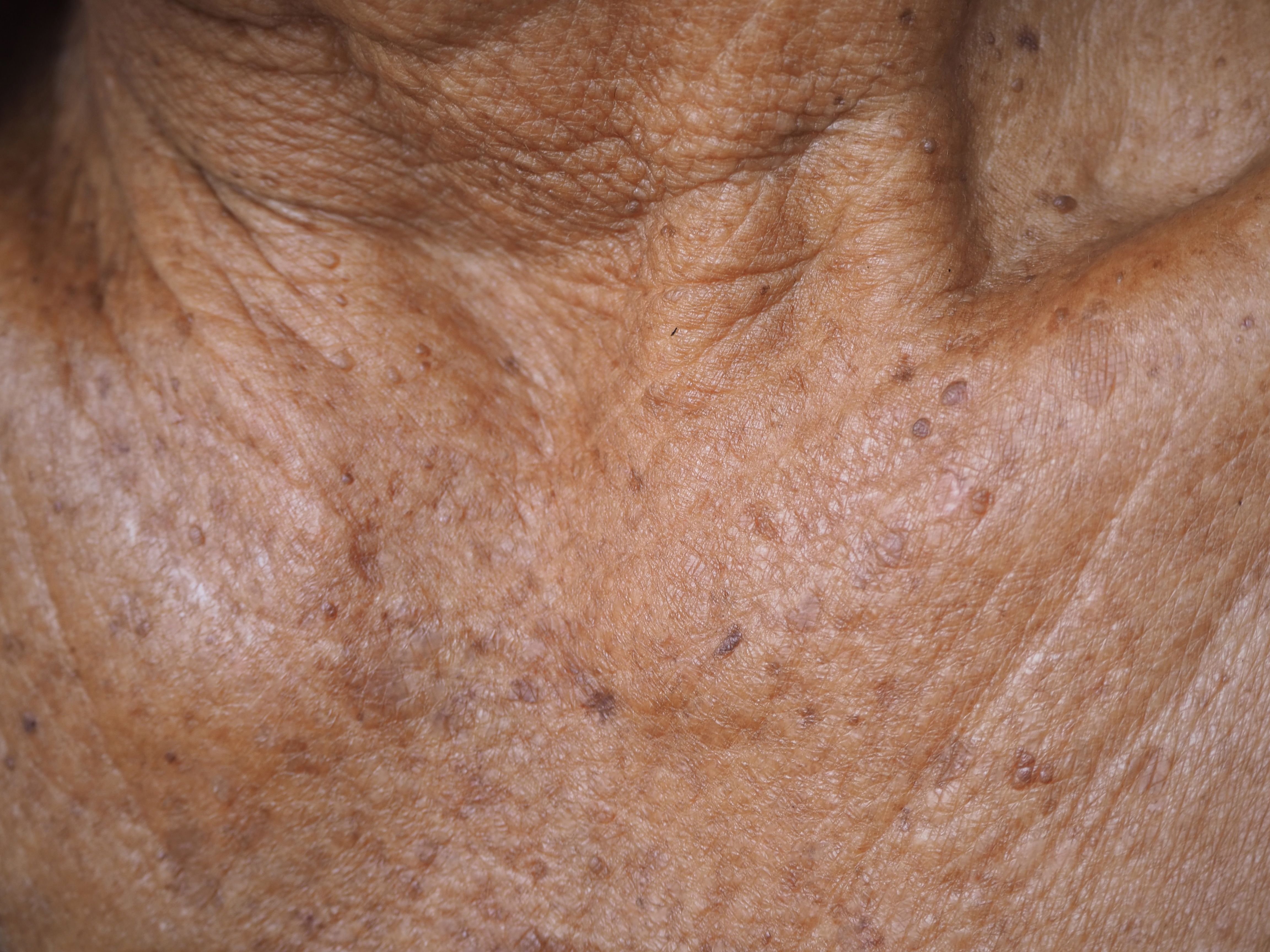

“Dr Skin” completed his dermatology residency program almost 20 years ago. His successful practice in the Sun Belt serves many young and older patients. Because of the excessive sun exposure seen by many of his patients, 4 of every 10 patients present with a variety of signs of photodamage, many of whom are younger than 65. Most commonly, patients present with myriad actinic keratoses. In an ethical attempt to limit the number of required patient visits, Dr Skin will often treat 20 to 30 actinic keratoses in 1 visit. Unfortunately, as would be expected, such patients continue to contract further actinic keratoses and sometimes reappear in his office every 2 months for treatment.

Dr Skin has taken courses on proper coding and codes in a recognized, honest, and ethical manner. Unfortunately, some of his third-party carriers have now informed him that only 15 actinic keratoses can be treated at each visit and only 4 such visits are allowed during a year for each patient. Dr Skin is aghast. He demands a rehearing by the carriers only to find that his pleas for appropriate reimbursement are unheard. His contention that the carrier is practicing medicine; that such an approach is poor quality of care; that forced undertreatment by him will lead his patients to contract squamous cell carcinoma, as he is of the view that solar keratoses represent incipient squamous cell carcinoma; and that such squamous cell carcinoma may lead to metastatic disease and death did not change the views of his carrier. How could this happen?

In 1996, the United States spent 14.2% of its gross domestic product on health care. In 2022, that increased to 17.3%. In fact, over the past year, US health care spending increased by 4.1% over the previous year, reaching $4.5 trillion ($13,493 per person). The United States is the highest spending country worldwide when it comes to health care. By 2031, it is expected that US health care expenses will be approximately 20% higher.1

Of note, life expectancy over 65 years in the US is increasing, and these are the very people who contract solar keratoses. Thus, their increasing numbers simply add to the health care costs of the US. It is argued that by controlling physician visits by such patients and limiting the number of treated lesions per visit, one can control spiraling health care costs.

Does such rationing work?

The Oregon Health Plan (OHP) was the first large-scale plan to ration health care coverage in this country. Under this plan, Oregonians who receive health care through the state’s Medicaid plan would receive health care services through a rationing plan. Medicaid coverage would be only for certain services. The Oregon legislature hoped that by “prioritizing” or “allocating” (both phrases preferred over “rationing”) services, it could reduce excess spending, allowing a “more sensible, systematic, and utilitarian manner—benefiting the greatest number of recipients possible within limited resources.” Did the plan succeed?2

The OHP did succeed in providing more of Oregon’s underserved population with health insurance, but it did not necessarily succeed in cutting health care costs at the same time.2 Nevertheless, over the past 3 decades, many states have tried to rein in the number of actinic keratoses to be treated. Florida mandated that topical chemotherapeutic agents are required before surgical removal of actinic keratoses. In addition, a set limit on the number of treated lesions would be required. The Medicare carrier stated that such measures were required because Florida was a leading state in the treatment of solar keratoses. The counterargument that so many older White Americans live in Florida fell on deaf ears.

One week after the Florida policy was promulgated, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) filed a lawsuit, seeking a temporary restraining order and a preliminary and permanent injunction. On August 7, 1997, the US Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit affirmed the trial court’s dismissal of the case against the Florida policies. Over the past several years, other states have joined Florida with such rigid requirements. Recently, the AAD supported a congressional resolution that will liberalize and nationalize treatment guidelines for such treatments. The issue has yet to be resolved.3

Dr Skin will not be reimbursed for his “excessive” treatments. Unfortunately, the policies limiting the amount of actinic keratoses treated in 1 year will not shield him from a medical malpractice case should he choose not to treat his patients, as would be required by the duty of reasonable care. Lack of reimbursement for procedures does not provide for such a shield.

References

1. National health expenditure data. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Updated December 13, 2023. Accessed January 10, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/historical

2. Oregon Health Insurance experiment. National Bureau of Economic Research. Accessed January 10, 2024. https://www.nber.org/programs-projects/projects-and-centers/oregon-health-insurance-experiment?page=1&perPage=50

3. Treatment of actinic keratosis. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed January 10, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=129

David J. Goldberg, MD, JD, is medical director of Skin Laser and Surgery Specialists of New York and New Jersey; director of cosmetic dermatology and clinical research at Schweiger Dermatology Group in New York, New York; and clinical professor of dermatology and past director of Mohs Surgery and Laser Research at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, New York.