- General Dermatology

- Eczema

- Alopecia

- Aesthetics

- Vitiligo

- COVID-19

- Actinic Keratosis

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Rare Disease

- Wound Care

- Rosacea

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Skin Cancer

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Drug Watch

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Acne

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Practice Management

Expert Insights on AAD’s Updated AD Management Guidelines for Using Phototherapy and Systemic Therapies

From the December cover feature: Christopher Bunick, MD, PhD; Aaron Drucker, MD, ScM; and Mona Shahriari, MD, share their thoughts on AAD’s updated atopic dermatitis guidelines.

Delmaine Donso/AdobeStock

The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) recently published new recommended guidelines for the management of atopic dermatitis (AD) using phototherapy and systemic therapies to include more recently approved biologics and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. After their comprehensive review, the guideline authors strongly recommend the use of dupilumab (Dupixent), tralokinumab (Adbry), baricitinib (Olumiant), abrocitinib (Cibinqo), and upadacitinib (Rinvoq); conditionally recommend phototherapy, cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil; and do not recommend systemic corticosteroids.1

“These guidelines give dermatologists a trustworthy source of evidence-based guidance to treat patients with more severe or refractory atopic dermatitis. We evaluated the evidence using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation approach so dermatologists and others can transparently assess the different treatment options; they can understand the quality and certainty of the evidence underpinning our recommendations. The guidelines are not meant to be prescriptive or mandate how a physician should treat individual patients. Physicians can incorporate the guidelines into their shared decision-making process with patients to create treatment plans that work for them,” said Aaron Drucker, MD, ScM, FRCPC, a board-certified dermatologist and physician-scientist at the Women’s College Research Institute in Toronto, Canada, an associate professor of dermatology at the University of Toronto, and one of the authors of the 2023 AAD guidelines.

AAD’s new guidelines update the previous 2014 recommendations of AD management for adult patients who do not respond to topical therapies.2

“The 2014 guidelines did not include biologics or JAK inhibitors—2 classes of medicines whose efficacy and safety have revolutionized the dermatologist’s approach to managing patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. Importantly, the AAD now strongly recommends in favor of using biologics (dupilumab, tralokinumab) and small-molecule JAK inhibitors (abrocitinib, upadacitinib, and baricitinib, although the latter is approved for AD only in Europe), based on moderate certainty of evidence. The new guidelines appropriately position the innovative, targeted therapeutics ahead of broadly immunosuppressive, nontargeted therapies. Due to low or very low certainty of evidence, phototherapy, azathioprine, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil all received a conditional recommendation in favor of use. Conditional positioning of these traditional immunosuppressives is consistent with a recent study showing they may be less safe than JAK inhibitors,3 although further evaluation in dermatologic disease populations is needed,” said Christopher Bunick, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology and physician-scientist at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

A multidisciplinary work group completed a systematic evidence review process by identifying and prioritizing clinical questions and outcomes, completing systematic retrieval and assessment of evidence, and assessing the certainty of the evidence and formulation of recommendations. Evidence of the effectiveness and safety of phototherapy and systemic therapies was determined from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

“Guidelines are important to guide treatment decisions but are also important from an insurance coverage standpoint. These updated guidelines validate the clinical decisions that I have been making in clinical practice and give me the confidence to continue to prescribe biologics and JAK inhibitors over traditional systemics and phototherapy. But importantly, from an access standpoint, some insurances require multistep therapy with traditional systemics before approving a biologic or JAK inhibitor for AD. These updated guidelines have the potential to aid clinicians in appealing inappropriate step therapy requirements and can ultimately result in patients gaining access to biologics and JAK inhibitors as first-line therapies for AD,” said Mona Shahriari, MD, board-certified dermatologist and assistant clinical professor of dermatology at the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, and associate director of clinical trials at Central Connecticut Dermatology Research.

What Recommendations Are New?

Monoclonal Antibodies

Dupilumab and tralokinumab are both FDA-approved biologics for the treatment of AD in adults, with overall strong efficacy and safety data. According to the guidelines, dupilumab at standard dosing (600 mg subcutaneously at initiation, then 300 mg every 2 weeks) is slightly less efficacious than higher doses of JAK inhibitors but has better efficacy than abrocitinib100 mg daily and comparable efficacy to upadacitinib15 mg daily. The work group surveyed its members on their favorite first-line systemic agent, and all members favored dupilumab.

Tralokinumab at standard dosing (600 mg at initiation, followed by 300 mg every 2 weeks) significantly improved the signs and symptoms of AD and quality of life in multiple clinical trials and had no major safety signals, similar to dupilumab. Currently, there are no head-to-head studies comparing tralokinumab with any other systemic therapies.1

JAK Inhibitors

Numerous JAK inhibitors are approved or are being studied for the treatment of AD, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, alopecia areata, and inflammatory bowel disease. Upadacitinib and abrocitinib are 2 selective JAK inhibitors approved for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe AD whose other systemic therapies have failed, such as immunosuppressants, corticosteroids, antimetabolites, and injectable biologics. According to the guidelines, in most cases, upadacitinib and abrocitinib are not commonly considered first-line systemic therapies. However, both JAKs demonstrate high efficacy at reducing signs and symptoms of AD, with rapid onset of action in phase 3 clinical trials. Higher doses of upadacitinib (30 mg daily) and abrocitinib (200 mg daily) show the highest efficacy at reducing EASI scores up to 16 weeks compared with all currently available treatments and were superior to dupilumab in head-to-head clinical trials.

Baricitinib is currently approved for the treatment of AD in Europe but is not yet FDA approved in the US for AD. “While no head-to-head clinical trials were done, network meta-analysis suggests baricitinib is less efficacious than upadacitinib and abrocitinib,” wrote the guideline authors.

As often discussed with JAK inhibitors, AAD’s guidelines reference boxed warnings that are now included with JAK inhibitors after a rheumatoid arthritis trial of tofacitinib (Xeljanz) reported major adverse cardiovascular events and malignancies in patients 50 years and older. Clinicians should be aware of the risks associated with JAK inhibitors so they can properly address patient concerns and provide clarity into the reasoning behind the boxed warning.1

Antimetabolites and Immunosuppressants

Cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil were conditionally recommended based on low or very low certainty evidence. According to the guidelines, in one head-to-head clinical trial, cyclosporine was more effective than methotrexate for up to 16 weeks, after which they were similarly effective. In another clinical trial, azathioprine and methotrexate had almost identical efficacy through 12 weeks of treatment. In a network meta-analysis, cyclosporine dosed between 3 and 5 mg/kg per day was more effective than methotrexate and azathioprine. There is even less RCT evidence supporting the use of mycophenolate mofetil.

Cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil require baseline and ongoing laboratory monitoring for adverse effects. Cyclosporine is commonly associated with renal impairment and hypertension, methotrexate is associated with liver damage, and azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil are associated with cytopenias.1

Phototherapy

According to the guidelines, phototherapy using UV radiation is effective for skin conditions such as psoriasis, AD, and cutaneous lymphomas, and although it has been used for decades, “there are few modern, high-quality RCTs evaluating the efficacy and safety of phototherapy for AD.” A Cochrane review was commissioned to support the AAD’s updated guidelines and included 32 clinical trials with 1219 randomized patients. Narrowband UV-B (313 nm wavelength) was the most studied treatment (13 clinical trials), followed by 6 clinical trials of UV-A1 (340-400 nm) and 5 clinical trials of broadband UV-B (290-320 nm).

“Narrowband UV-B is the most widely used form of phototherapy; this may be because of its established efficacy for psoriasis and safer track record than UV-A1 and broadband UV-B,” wrote the guideline authors.

The guidelines noted that potential adverse effects of phototherapy include sunburn like reactions, intolerance due to heat from the light source, and risk of skin cancer due to UV radiation exposure. Additionally, one pitfall of phototherapy is accessibility, according to the guidelines.1

Systemic Corticosteroids

The guideline authors conditionally recommend against the use of systemic corticosteroids for the management of AD due to the substantial risk of serious adverse events, even during short-term treatment.1

“A very important declaration in the AAD 2023 AD guidelines is the conditional recommendation against systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of AD. In some analyses, as many as 50% of all patients with AD and 75% of all moderate to severe patients with AD received oral systemic corticosteroids.4 Oral corticosteroids provide short-lived and usually ineffective therapy for moderate to severe patients with AD and have the highest adverse event rate with respect to malignancy (without non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC)), NMSC, and major adverse cardiac events.3 These new guidelines position oral steroids as a therapy of last resort for patients with AD,” said Bunick.

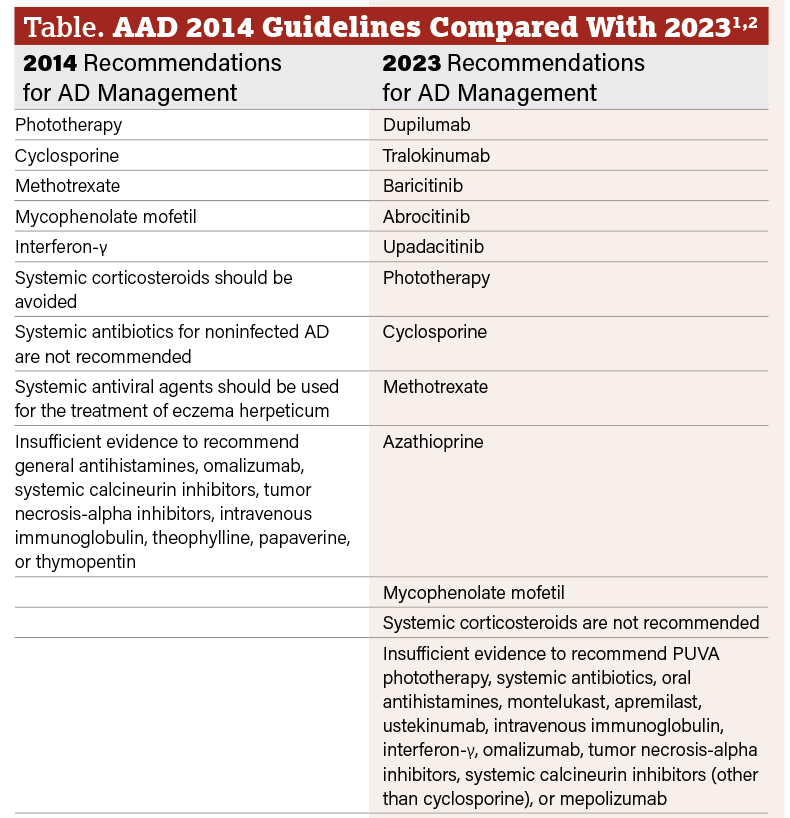

What Has Changed Since 2014?

Click table to enlarge

The most important change in the 2023 AAD guidelines is the addition of recommended biologics and JAK inhibitors for adults with AD. Biologics dupilumab (FDA-approved in 2017) and tralokinumab (FDA-approved in 2021) are both new AD agents that were approved after AAD’s 2014 guidelines. JAK inhibitors abrocitinib and upadacitinib were approved by the FDA in 2022, and baricitinib is used off-label for AD as it is not yet approved in the US for AD.

The 2014 guidelines suggested interferon-γ (IFN-γ) can be considered as an alternative therapy for refractory AD in adults and pediatric patients who have not responded to or have contraindications to other systemic therapies or phototherapy. However, the 2023 guidelines state that there is insufficient data to recommend IFN-γ.

Both guidelines continue to conditionally recommend the use of phototherapy, cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, and mycophenolate mofetil, as well as recommend against the use of systemic corticosteroids due to the adverse effects associated with both short-term and long-term use. (Table)1,2

“The last iteration of the AAD guidelines on systemic treatment for atopic dermatitis was published in 2014. Since then, 4 new systemic treatments have been approved in the US, so an update was definitely needed. When the last guidelines were published, only nontargeted, off-label systemic medications were available,” said Drucker. “We now have 2 biologics and 2 JAK inhibitors approved, backed by large phase 3 clinical trials. We have substantial evidence to recommend these medications to treat atopic dermatitis. Essentially, there is a whole new treatment paradigm for atopic dermatitis that was initiated in 2017 with the approval of dupilumab, with more amazing advances since and more to come.”

Additional Considerations

Patients With Skin of Color

Although not mentioned in the new guidelines, specific treatment considerations for patients with skin of color with AD are crucial. AD often does not present with common erythema in patients with skin of color, and AD is more likely to cause dyspigmentation in patients with skin of color than patients with lighter skin tones.5

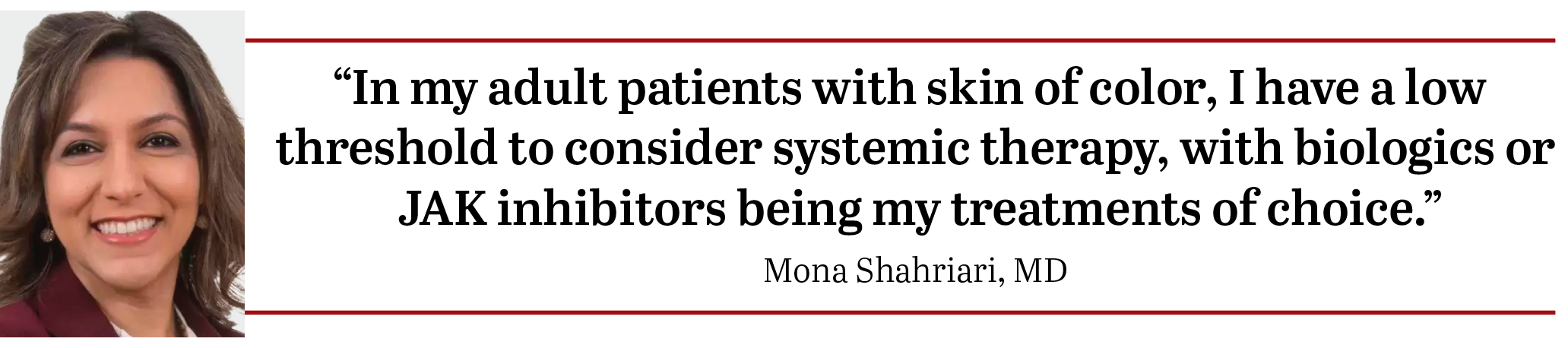

“In my adult patients with skin of color, I have a low threshold to consider systemic therapy, with biologics or JAK inhibitors being my treatments of choice. In this population, the postinflammatory pigment alteration from AD can often be more troubling than the disease itself. With every scratch comes the potential for more pigmentary sequelae, so my goal is to get the AD under control quickly so we can not only prevent further pigmentary changes but allow the active pigmentary changes to resolve. When it comes to topical therapies, I limit the use of topical corticosteroids due to concerns about hypopigmentation at the site of application. The nonsteroidal topical ruxolitinib is a great option, as it offers high levels of efficacy both from an itch and skin clearance standpoint but does not compromise the skin pigmentation,” said Shahriari.

She added, “However, access can oftentimes pose a challenge in my patients with skin of color, given their higher likelihood of having government-funded insurance that precludes the use of co-pay cards. Finally, I am reluctant to recommend phototherapy for my patients with melanin-rich skin because melanin acts as a UV filter, which means higher doses of phototherapy with longer exposure times may be required for optimal responses. Moreover, tanning is a known side effect of phototherapy, which can be problematic in patients with skin of color who come from cultural backgrounds where fair skin is valued and darker skin is stigmatized.”

Updates From the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology

“Interestingly, there are similarities and differences between the new AAD 2023 AD guidelines and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) 2023 AD guidelines. The AAD and AAAAI are similar in that they both strongly recommend in favor of using biologics (dupilumab and tralokinumab). Surprisingly, the AAAAI only conditionally recommends in favor of JAK inhibitor use in moderate to severe AD; they cite low certainty of evidence while the AAD strongly recommends in favor of JAK inhibitor use citing moderate certainty of evidence. The difference in opinion on JAK inhibitors may positively reflect how far dermatologists have come in their knowledge, use, and comfort level with JAK inhibitors in their clinical practice over the past 2 years,” said Bunick.

He added, “One specific area of transformation in dermatology has been increased communication with patients regarding the purpose and implications of boxed warnings. Much like the AAD or AAAAI AD guidelines, a boxed warning itself is a guide to clinicians and patients on how to mitigate risk, select proper patients, and monitor for adverse events. Patients gain a sobering perspective when they learn that over the counter ibuprofen carries a boxed warning for some similar potential adverse events as JAK inhibitors. AAAAI also goes further than the AAD guidelines in downgrading the traditional immunosuppressives: Only cyclosporine received conditional recommendation in favor of use by the AAAAI, whereas azathioprine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil all received conditional recommendations against use. Like the AAD, the AAAAI also conditionally recommended against oral systemic steroids.”

Real-World Opinions

As experts in supporting patients with inflammatory skin conditions, Bunick, Drucker, and Shahriari shared their real-world opinions of the updated AAD guidelines for the management of AD.

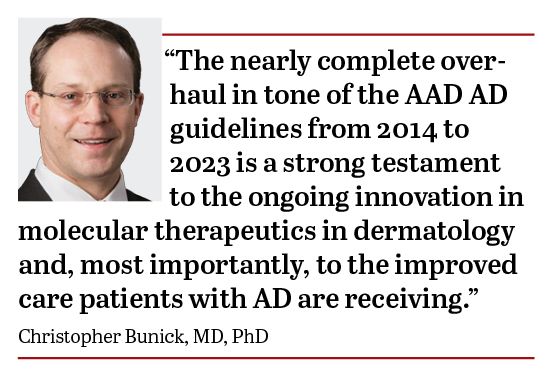

“Together, the AAD and AAAAI 2023 AD guidelines position advanced therapies targeting AD cytokines at the top of the treatment algorithm while relegating excessively broad, nontargeted, and higher-risk therapies to patients who fail biologics and/or JAK inhibitors. The nearly complete overhaul in tone of the AAD AD guidelines from 2014 to 2023 is a strong testament to the ongoing innovation in molecular therapeutics in dermatology and, most importantly, to the improved care patients with AD are receiving,” said Bunick.

“At this point, dupilumab is my first-choice systemic medication for most patients. It is very effective (the most effective biologic available for atopic dermatitis so far) and has been around for over 6 years with an excellent safety profile. JAK inhibitors upadacitinib and abrocitinib have amazing efficacy, particularly at higher doses, but there are more potential safety concerns. Those concerns are mostly based on data from other JAK inhibitors (eg, tofacitinib) used in other patient populations (eg, older rheumatoid arthritis patients), but we should still be aware of those concerns and counsel patients about them,” said Drucker.

“For my patients with atopic dermatitis, I almost exclusively use both the biologics and the JAK inhibitors (only upadacitinib and abrocitinib since baricitinib is not currently FDA-approved for AD in the US). These targeted therapies are FDA-approved for AD, have been studied in large-scale clinical trials, offer high levels of efficacy with respect to skin clearance and itch control, and have a tolerable safety profile both in the short term and the long term. As such, they are my first-line agents for the treatment of AD. I have extensive experience with our FDA-approved biologics and JAK inhibitors, and I find the majority of patients are satisfied with both classes of therapeutics. In patients who are looking for a treatment that does not require initial or ongoing bloodwork, is not administered daily, or in individuals who are at high risk of serious or recurrent infections, biologics are my treatment of choice. These patients say that they can ‘inject and forget.’ In patients in which the speed of efficacy is important, meaning we need to cool down the AD quickly, or in patients that are looking for high levels of skin clearance and itch improvement in record time, I gravitate toward the JAK inhibitors. For the first time in my career, I have had patients who started a JAK inhibitor for their AD call me to tell me about the ‘unreal’ speed at which their symptoms improved,” said Shahriari.

She added, “If a patient tries and fails all FDA-approved options, I consider going back to basics and trialing traditional systemics like cyclosporine, methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate. However, given that these agents are broadly immunosuppressive and not targeted to the specific pathophysiologic pathways of AD, I have a higher concern for unwanted effects, like potential end-organ toxicity with long-term use. Interestingly, newer data suggests our JAK inhibitors, despite their warnings, may be safer than traditional systemics. I seldom use systemic corticosteroids for AD, given the significant risk of adverse events even with short-term use and the potential for rebound of the AD upon discontinuation of therapy.”

References

1. Davis DMR, Drucker AM, Alikhan A, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with phototherapy and systemic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol.2023;S0190-9622(23)02878-5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.08.102

2. Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):327-349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030.

3. Daniele S, Bunick C. JAK inhibitor safety compared to traditional systemic immunosuppressive therapies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21(12):1298-1303. doi:10.36849/JDD.7187

4. Meyers KJ, Silverberg JI, Rueda MJ, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism among patients with atopic dermatitis: a cohort study in a US administrative claims database. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(3):1041-1052. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00538-4

5. Adawi W, Cornman H, Kambala A, Henry S, Kwatra SG. Diagnosing atopic dermatitis in skin of color. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41(3):417-429. doi:10.1016/j.det.2023.02.003

AAD recently released the session schedule for the 2024 Annual Meeting in San Diego, California, held March 8-12, 2024. There are numerous opportunities to discover atopic dermatitis treatment pearls, learn how to incorporate these new guidelines, and challenge your approach to difficult cases. If you are attending, we would love to connect! Email us at DTEditor@mmhgroup.com and visit our booth in the exhibit hall.