- General Dermatology

- Eczema

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Alopecia

- Aesthetics

- Vitiligo

- COVID-19

- Actinic Keratosis

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Rare Disease

- Wound Care

- Rosacea

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Melasma

- NP and PA

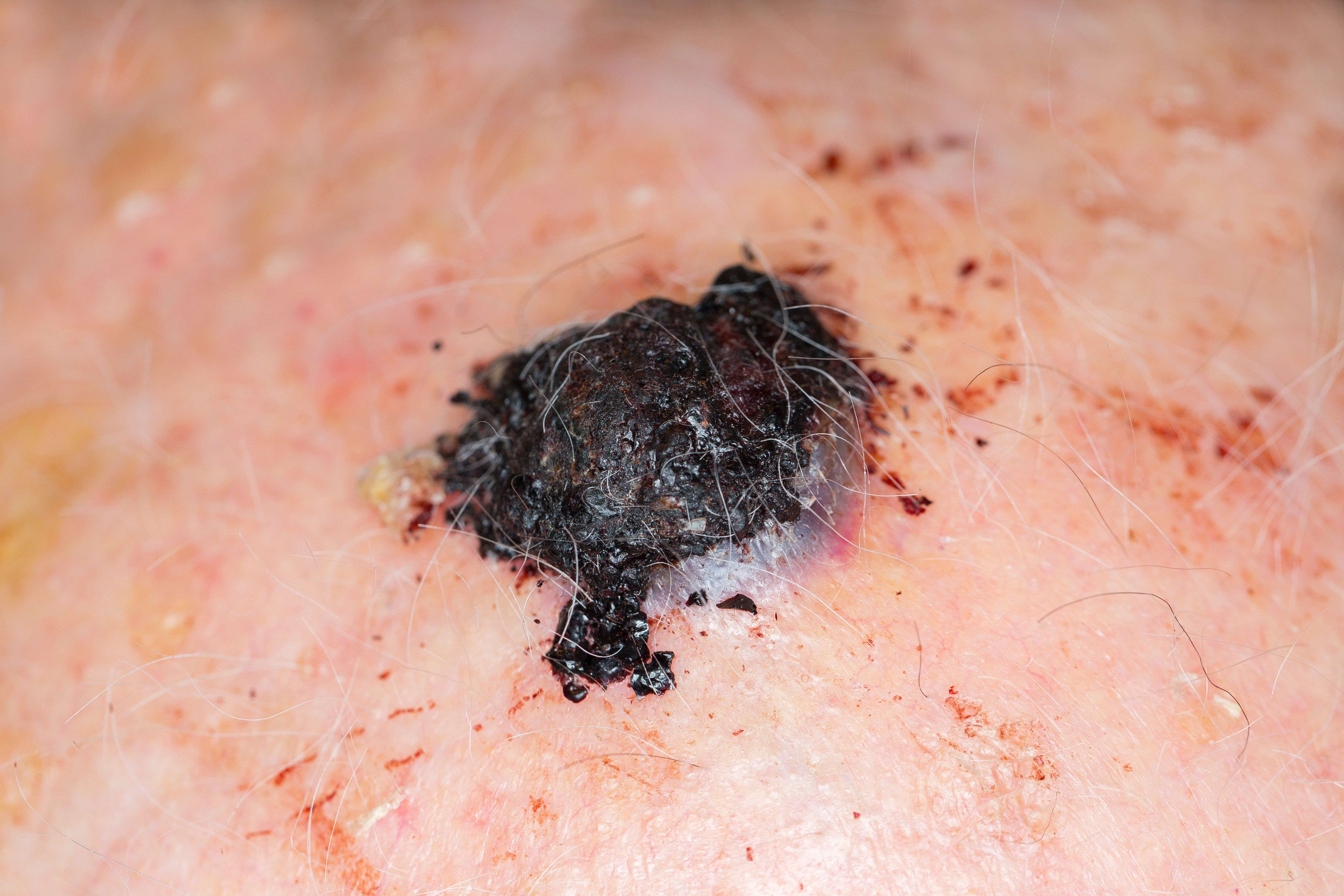

- Skin Cancer

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Drug Watch

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Acne

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Practice Management

- Prurigo Nodularis

Publication

Article

Standard of care for primary cutaneous melanoma evolves

Author(s):

Though still considered controversial, several evolving treatment and management plans for primary cutaneous melanoma are making their way into the mainstream and challenging more traditional approaches.

Dr. Council

Though still considered controversial, several evolving treatment and management plans for primary cutaneous melanoma are making their way into the mainstream and challenging more traditional approaches.

RELATED: Nanovaccine shows promise for melanoma

“The standard of care for primary cutaneous melanoma may slowly be changing in light of the recent advancements and positive outcomes we are seeing with Mohs surgery, slow Mohs and new genetic molecular tests for diagnosis and prognosis of the tumor,” says M. Laurin Council, M.D., FAAD, FACMS, associate professor of dermatology, John T. Milliken department of internal medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis.

Mohs surgery is generally accepted for melanoma in situ on the head and neck; however, the consensus is not as clear when it comes to invasive cutaneous melanoma, she says. A wide local excision of invasive melanoma with margins from 1 cm to 2 cm remains the standard of care; but, recent data indicate that Mohs surgery can achieve treatment outcomes equal, if not better than, the traditional wide local excision technique in early-stage invasive melanoma, she says.

Moreover, Mohs surgery used in invasive melanoma has also been shown to result in lower recurrence rates compared to a standard wide local excision, especially on the head and neck.

Removing a melanoma with these wide margins can be challenging in certain areas, such as the eyelid or nose where less tissue is available. In these areas, Dr. Council says that surgeons may rely on the disclaimer in current guidelines that allows for removing less tissue in these complex areas. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines state that a surgeon may modify margins for an individual due to anatomic or functional considerations.

“Many Mohs surgeons today are adjusting their focus and believe that the importance is not necessarily the size of the margin; rather, that you clear the entire primary tumor,” she says. “Accordingly, the ‘standard margin’ can change depending on the individual case, and treatment outcomes can be achieved that are comparable to those of the traditional wide local excision technique.”

RELATED: GEP testing promising in melanoma

Some obstacles remain for clinicians who may want to offer Mohs surgery to their patients, Dr. Council adds. Not all centers are set up for immunohistochemistry, and not all histotechnicians are comfortable cutting sections very thinly to be able to perform the immunostaining.

Although most Mohs surgeons likely do not offer traditional Mohs surgery for melanoma, Dr. Council says they do often perform “slow Mohs” for melanoma, which is a variation in which the tumor is removed and processed with permanent sections (instead of frozen) in a manner that allows for complete evaluation of the margins.

“Using Mohs surgery for primary melanoma still remains somewhat controversial because there are some surgeons who are taking less than a 1 cm margin, which is considered the standard of care, whenever possible,” Dr. Council says.

For prognostic purposes, genetic tests such as DecisionDx-Melanoma test (Castle Biosciences, Inc.) and the SkylineDx (currently in trials) can help indicate whether a tumor is at high or low risk for metastasizing sometime in the future.

Ideally, the thought is that these molecular assays could be implemented instead of necessarily performing a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB).

RELATED: Mechanisms driving melanoma immunotherapy

According to Dr. Council, SLNB is also slowly evolving because of recent data showing the same survival for melanoma patients who received SNLB with and without complete lymphadenectomy. As a result, some surgeons may do SNLB for prognostic information Dr. Council said, but they will not necessarily go back and perform a complete lymphadenectomy.

“Particularly for melanoma of the head and neck, where the lymphatic drainage is more variable and there is a higher rate of false negativity, perhaps a genetic test would be more appropriate,” Dr Council says. “As the SLNB is an imperfect test, there is a vacuum to fill and a genetic test that is superior in outcomes and less invasive than SNLB could be ideal. Ultimately, with our choices, we hope to minimize the morbidity for patients and give them equivalent or superior outcomes.”

Disclosures:

Dr. Council reports that she is a consultant for Sanofi-Genzyme/Regeneron.